SPECIAL REVELATION

We previously said that the term “revelation” can be understood in its broad sense as a “communication from God” or its narrow sense as the “disclosure of something previously unknown.”

These few segments about Jesus’ resurrection are part of what theologians call “special revelation.” This is revelation about God that is not readily apparent to the every person. We said there are three different kinds of what theologians call “special revelation”:

• The revelation of Jesus Christ

• Scripture

• Particular revelation to individuals

The most important of these is the revelation of Jesus Christ. This includes the understanding that Jesus of Nazareth was more than a good man or wise teacher: He was the Son of God. How do we know this? Well, there is reliable historical evidence for the resurrection of Jesus from the dead.

“THREE KEY ASPECTS” OF THE RESURRECTION NARRATIVE

We are presently looking at “three key aspects” of the resurrection narrative. The question before us would be, “Is the resurrection of Jesus the best explanation for these three phenomena?”

1. The empty tomb was discovered by a group of his women followers three days after the crucifixion (Sunday).

2. There were post-mortem appearances of Jesus to various people over a 40-day period.

3. There was NO existing tradition in the culture of that day about an individual being resurrected.

So we need to (1) examine how accurate these three facts are and then (2) weigh the resurrection narrative against competing theories to see if they are more plausible.

REVIEW

What we’ve learned so far:

1. Three blogs before this one, we established that Jesus died and was buried in Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb.

2. Two blogs ago, we demonstrated that Jesus’ tomb was found to be empty by a group of his women followers.

3. In the last blog, we clearly established that there were post-mortem appearances of Jesus to various people.

There were multiple, independent sources within the first few years after Jesus’ death who attested to all three of these facts. At this website, we think that Jesus’ resurrection is the best explanation for all three of these facts.

We now want to look at the third key aspect of the resurrection narrative: Was there any existing tradition in the culture of first-century Palestine that would explain how a story about an individual being resurrected might have gotten started?

THE OLDEST KNOWN ORAL TRADITION GIVEN TO PAUL WITHIN TWO YEARS OF JESUS’ DEATH

We start again with 1 Corinthians 15:3-8 (RSV). Paul tells the believers at Corinth, Greece:

“3 For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received, that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures,

4 that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures,

5 and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve.

6 Then he appeared to more than five hundred brethren at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep.

7 Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles.

8 Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me. ”

This was definitely an authentic letter written by Paul and the oldest known teaching in the entire New Testament. It was astounding for a former Jewish zealot who put Christians to death to suddenly claim that he too had seen a post-mortem appearance of Jesus and then to abruptly become just as zealous in defending Christianity.

Regarding this passage in 1 Corinthians 15, we have examined its claim that Jesus died and was buried. We’ve examined its claim that there were resurrection appearances to several people.

THE ORIGIN OF THE RESURRECTION NARRATIVE

Even the most skeptical New Testament scholars are forced to recognize that the earliest Christians, at the very least, believed that Jesus had been raised from the dead.

At this point, we want to determine if it’s possible that the story of an individual being resurrected simply arose as legendary embellishment from the existing culture of first-century Palestine. Any historian would be inclined to ask if that was the case. There were three main cultures in Palestine that had any influence on peoples’ thinking at that time:

1. Christianity,

2. Paganism and

3. Judaism.

CHRISTIANITY

Would there have been enough time in the three years of Jesus’ ministry for Christian myth or legendary embellishment to develop regarding the resurrection of Jesus?

By the time of his death, there were obviously people in Palestine who were devoted followers of Jesus. Many miracles had been performed. He had established correct doctrine and showed them how they ought to live. But there was something more thing to be done. He knew that he had to atone for the sins of mankind through the sacrifice of his own life, and he had to conquer death and arise victorious over the grave.

However, the Church that would arise after Jesus’ brief three years of ministry had not been fully formed, the Great Commission to spread the gospel had not been given, the gift of the indwelling Holy Spirit had not yet been imparted to believers, the gospels and epistles of the New Testament had not been written. Christianity, in a formal sense, did not yet exist.

At the time of his death, it would have been impossible for this nascent movement to be the source of an already existing myth or tradition about the individual resurrection of Jesus. We say this because the normal rate of legendary development, which we discussed in an earlier blog, would require two generations to pick up enough steam to fabricate a myth about Jesus. For example, the apocryphal gospels, which were largely myths of incredible proportion, were not written until the second century, and Jesus died around 33 A.D.

PAGANISM

Were there pagan influences on Christian disciples in first-century Palestine that would explain where this story about Jesus’ resurrection came from?

In the 1890s and for part of the twentieth century, there were attempts by German protestant scholars of comparative religion in the History of Religion school to actively look for parallels between Christianity’s belief in Jesus’ resurrection and similar narratives within pagan mythology from centuries earlier. This was called the Christ Myth theory: the proposition that Jesus of Nazareth never existed or, at least, had nothing to do with founding Christianity.

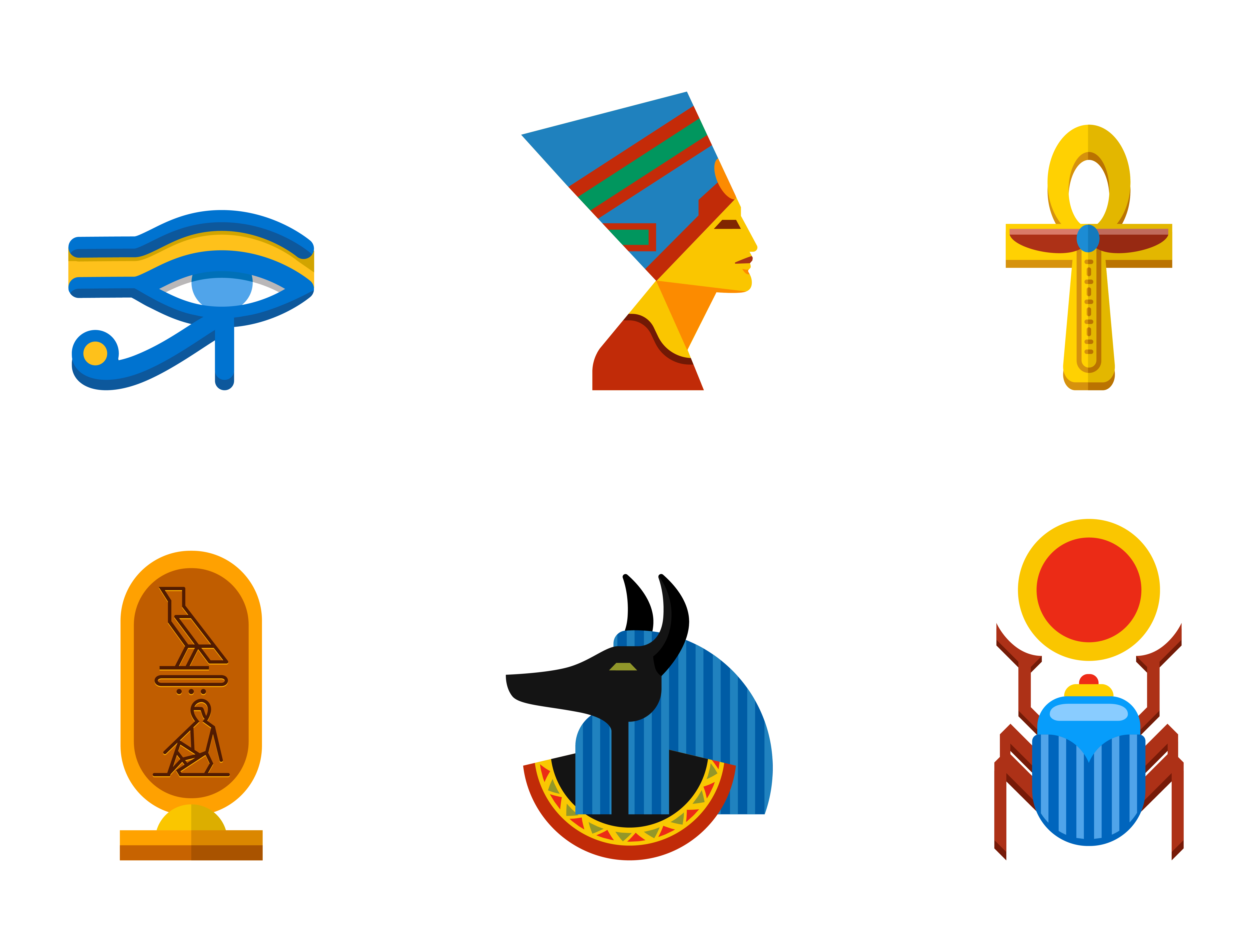

As one example, in ancient Egypt there was one myth about the god Osiris that followed the farming cycle on the Nile River. Egyptians believed that cutting down barley and wheat represented the death of Osiris, and sprouting shoots was based on Osiris’ ability to resurrect the farmland. Some people believed that there was a celebration on the third day after his death saying “Osiris has been found.” However, in the mythical story, Osiris did not come back to life at all. He continued to exist among the departed in a realm far removed from this reality on earth.

Sometime in the 1900s, the Christ myth movement collapsed and was abandoned for a couple of reasons:

1. This was partly because of the abundance of gods and heroes in the ancient world and the sloppy manner in which these scholars had attempted to draw parallels with historic pagan myths about figures who were actually involved in disappearance stories (e.g., the hero vanishes), political stories of emperor worship (e.g., Julius Caesar, Caesar Augustus), assumptions into heaven (e.g., like Hercules and Romulus) or seasonal symbols for the crop cycle (e.g., vegetation dies in dry season and comes back to life in the rainy season).

2. No one has yet been able to find a causal connection between pagan mythology and how the story of Jesus’ resurrection originated among Christian disciples of first-century Palestine. The Jewish people of that day knew about seasonal gods as described in Ezekiel 8:14-15 and found these stories to be detestable.

After a while, it became clear that none of these pagan stories were actually about resurrection from the dead.

T.N.D. Mettinger states:

“From the 1930s . . . a consensus has developed to the effect that the ‘dying and rising gods’ died but did not return or rise to live again . . . Those who still think differently are looked upon as residual members of an almost extinct species.”

Tryggve N. D. Meeting, The Riddle of Resurrection: “Dying and Rising Gods” in the Ancient Near East (Stockholm, Sweden: Almquist & Wiksell International, 2001), 4,7.

Commenting on theology’s abandonment of Christ myth parallels to pagan gods, Dr. William Lane Craig states:

“Here we see one of the major shifts in New Testament studies over the last century . . . Scholars came to realize pagan mythology is simply the wrong interpretive context for understanding Jesus of Nazareth . . . Jesus and his disciples were first-century Palestinian Jews, and it is against that background that they must be understood.”

William Lane Craig, Reasonable Faith (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2008), 391.

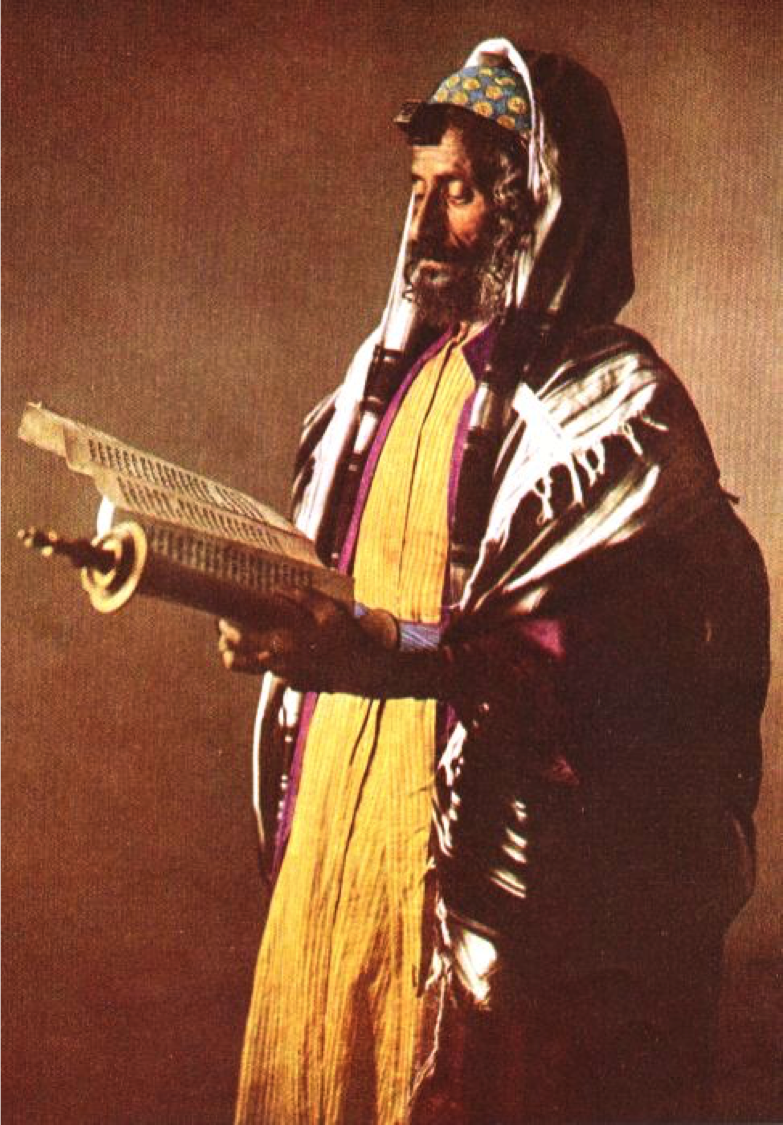

JUDAISM: THE HISTORICAL CONCEPT OF A TRIUMPHANT MESSIAH

As we examine cultural influences on first-century Palestine, we also need to ask if there were Jewish influences on Christian disciples in first-century Palestine that would explain where this story about Jesus’ resurrection came from?

For over 1,000 years, the Jewish people had believed in a concept of Messiah that was not even remotely related to the actual events of Jesus’ life.

“Messiah,” as perceived by the Jewish people, was to be a future conquering king who would annihilate his enemies, a triumphant figure who would be feared and respected by both Jew and Gentile. This messianic figure would establish the throne of David in Jerusalem, and the Jews would possess their promised land as its foremost power from that time forward. It was all about victory, dominance, royalty and crushing Messiah’s enemies under his feet.

That is what motivated the Jews when they sang praises, shouted “Hosanna” and laid palm leaves before Jesus as he triumphantly entered Jerusalem. At the very least, they expected Jesus to throw off the yoke of the Roman Empire and make the Jewish people the dominant power in Jerusalem and the promised land.

THE DEFEAT AND HUMILIATION OF CRUCIFIXION IN JEWISH CULTURE

On the other hand, crucifixion and being hung on a tree to die was proof to the average Jew that Jesus was “cursed by God” and just another failed Messiah who experienced a death of absolute humiliation and disgrace.This view is expressed in Deuteronomy 21:22-23:

“22 And if a man has committed a crime punishable by death and he is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, 23 his body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but you shall bury him the same day, for a hanged man is accursed by God; you shall not defile your land which the Lord your God gives you for an inheritance.”

First-century, traditional Jews who had no affiliation with Christianity believed that Jesus was “cursed by God,” an imposter who sought to be the conquering Messiah but failed in the attempt and suffered the worst humiliation for being so presumptuous.

This was just one failure in a string humiliating failures because there were lots of charlatans over the centuries who claimed to be the Messiah. Each time this occurred, it was humiliating to their followers as well. So traditional Jews would say just bury Jesus the same day in keeping with Deuteronomy 21and add his name to the long list of failed pretenders.

A DISASTER FOR THE CHRISTIAN DISCIPLES

For those three days after his death, even though Jesus had foretold his demise through veiled references, the Christian disciples who were sure of Jesus’ authenticity had to be confused and wonder what just happened. It didn’t square with what they’d been taught for most of their lives about the Jewish Messiah.

New Testament scholar and theologian N.T. Wright expressed it this way: “The crucifxion of Jesus, understood from the point of view of any onlooker, whether sympathetic or not, was bound to have appeared as the complete destruction of any messianic pretentions or possibilities he or his followers might have hinted at.”

N.T. Wright, Christian Origins and the Question of God, vol. 3: The Resurrection of the Son of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003), 557-558.

It’s difficult to exaggerate how disastrous this was for the disciples because, in growing up in Jewish culture, they never had been given any concept of a resurrection other than the general resurrection of the righteous at the end of the world.

JEWISH CONCEPT OF RESURRECTION

The Jewish people drew a clear distinction between:

1. “Resuscitation” – in which a person returns from death to this earthly life and their normal physical body that will eventually die (as in the story of the prophet Elijah and the young son of the widow of Zarapheth).

2. “Resurrection” – raising a person from the dead within the spacetime universe to a body they will have in eternity (as in the case of Jesus).

3. “Translation” – bodily assumption directly out of this world and into heaven (as in the stories of Enoch and Elijah).

The general resurrection is mentioned in Jewish scripture three times: Isaiah 26:19, Ezekiel 37 and Daniel 12:2.

The idea of a general resurrection of the righteous at the latter end of the world was a very familiar concept. It became a pervasive hope among the Jewish people during the “intertestamental period” (i.e., the 400 years from the time of Malachi in 420 B.C. to the time of John the Baptist in the early first century A.D., called by protestants “the 400 silent years or intertestamental period,” and by Catholics and Orthodox “the deuterocanonical period”).

Even though the Jews were filled with hope about the general resurrection during those 400 years, by the time of Jesus, they were divided into Pharisees who still had that hope and Saducees who denied the resurrection altogether.

The individual resurrection of Jesus differed from the Jewish concept of a general resurrection in two major ways:

1. For the Jewish people, resurrection was ALWAYS at the end of history or the world. There was no existing concept of a resurrection in history.

2. Jews only believed in a general resurrection of the righteous, or of all people to be judged, but the possibility of an individual resurrection was entirely foreign to them.

BIBLE EXAMPLES OF BELIEF IN A GENERAL RESURRECTION AT THE END OF HISTORY

In John 11:23-24 (ESV) when Jesus was about to resuscitate Lazarus and raise him from death, Jesus told Martha, “Your brother will rise again.” Martha responded, “I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.” She thought Jesus was talking about the end of the world, and she had no concept of a resurrection before that time.

During the three days after Jesus’ death, the disciples probably believed this same thing, that they would not see Jesus again until the general resurrection at the end. For example, when Jesus foretold his own resurrection in Mark 9:9-11, they did not understand what he was saying because they questioned what this particular “rising of the dead” might mean.

Before the end and general resurrection, they knew that Elijah had to return. So in Mark 9:9-11, the disciples asked Jesus, “Why do the scribes say that first Elijah must come?” They were talking about the great and terrible day or judgment day at the end of history and did not understand that Jesus was talking about his own individual resurrection before that time.

The disciples themselves really did not have a concept of an individual being resurrected in history. They ONLY believed in a general resurrection.

CONCLUSION

Regarding the resurrection narrative about Jesus, let’s return to our original question: Is it possible that the story of Jesus’ resurrection was a kind of legendary embellishment that could have had its origin in any of the following cultures in first-century Palestine:

• Christianity?

• Paganism?

• Judaism?

As we look for sources of potential legendary embellishment in these three cultures, it’s not plausible to suggest that a myth arose about Jesus’ resurrection within Christianity because:

• he had only been teaching the people for three years,

• his own disciples did not understand that he would individually be resurrected in their lifetimes, and

• Christianity itself did not really exist in a formal sense at the time of Jesus’ death — it was only after his resurrection that all the elements of the gospel were in place (see 1 Corinthians 15:3-8).

It also is not plausible to think that pagan traditions about their mythical gods and heroes provided any credible source for the origin of the idea that Jesus was resurrected. None of the pagan gods or heroes were ever raised from the dead.

In addition, Judaism could not possibly have provided myths or legends that served as the source for such an idea. Judaism drew a very clear distinction between resuscitation, resurrection and translation.They were very familiar with the idea of a general resurrection and judgment at the end of the world, but an individual resurrection prior to that time was entirely foreign to Jewish culture in first-century Palestine.

This belief in Jesus’ individual resurrection during their lifetimes did not really exist among the disciples at the time of Jesus’ death. The origin of this idea came directly from the disciples of Jesus only AFTER his actual resurrection!

It was at the point of Jesus’ resurrection that the full concept of the gospel of Christ became clear to them.

FURTHER READING

These information that there was no existing tradition in the cultures of first-century Palestine that could explain the narrative of Jesus’ ressurection was obtained from Dr. William Lane Craig in his book Reasonable Faith.

For further insight on the resurrection, read N.T Wright’s exhaustive study entitled The Resurrection of the Son of God.